In the history of a nation, it is the rise and its sustainability which are frequently recorded carefully. The decline and decay, however rapid or measured, are often glossed over. History is normally written by the victors. This forthcoming series details only a fraction of what actually happened, historically. The genocide of a nation which was once considered to be a super power and brought to its knees over the centuries, is strangely missing from the annals of history. Modern day historians, while acknowledging other smaller massacres which have happened on a global time scale do not enumerate the systematic decimation of the population of a nation, which at one time was largely Zoroastrian in Central Iran. The purpose of this article is not to attribute blame on any single group for the deeds of their ancestors, for which the current generation cannot be held responsible, but to highlight the holocaust which the Zoroastrian people went through, over the centuries. We as a community need to pause and reflect upon the single minded intention of our ancestors in preserving their religion in the land of its origin, despite unimaginable suffering, humiliation, torture and extermination. The customs and traditions as preserved by our forefathers have been whittled away, bit by bit, through the centuries. Perhaps when we realize what we have lost, can we truly appreciate the value of what we have inherited – a priceless heritage, both religious and cultural – which if frittered would wash away the sacrifices of our ancestors in the blood soaked sands of a nation that was once ours – the land of Airyana Vaeja – Ancient Iran!

The assassination of the last Sassanian King Yazdegird III (624 – 651 CE) at the hands of a miller in Merv, to loot his purse, clothes and jewellery, brought an end to the glorious Sassanian Empire in 651 CE. Such was the sad fate of the last Zoroastrian ruler in death, that it was a Christian Bishop, Mar Gregory, who buried King Yazdegird III. His son, Peroz III, and many others went into exile to China. Within a few generations, these Zoroastrians were lost, having mingled and assimilated with the local populace.

Most Parsis today believe that the Zoroastrian Empire then rapidly collapsed upon itself, the country subjugated under the Arab rule, and Islam replaced Zoroastrianism overnight. Nothing could be further from the truth. Iran fragmented and pockets of resistance developed. Many regions operated autonomously to a certain extent.

It took a good 200 years (6-7 generations) before Zoroastrianism slowly started receding as Islam crept into the land of the Aryans, one village at a time. About 130 total uprisings took place during this period and all of them were brutally subjugated. Infact, even in the mid-1500s there were more than 3 million Zoroastrians in Iran. However in the next 250 years, they had been whittled down to less than 50,000. Had a “Saoshyant” (Avestan meaning: “One who brings benefit”) in the form of Maneckji Limji Hataria from India not visited Iran shortly therein at that critical juncture, in all likelihood, Zoroastrianism would have been extinct in Iran, today.

Iran, or Greater Iran as it was then known, with its state religion Zoroastrianism formally established in 224 CE, covered large swaths of present day Iraq, Armenia, Georgia, Tajikistan, Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan and Afghanistan. In the seventh century, most of the inhabitants of Greater Iran were Zoroastrians, though Buddhism and Christianity had already made substantial inroads at its far borders. On the map, Greater Iran during the Sassanian rule was almost double in size to what it is now, having been carved down first by the Russians and later by the British, in the nineteenth century.

Sassanian Empire at its greatest extent

Sassanian Empire at its greatest extent

(Photo sourced from Wikipedia)

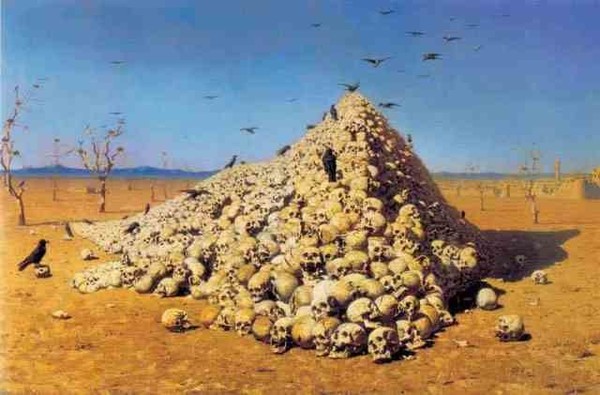

The bulk of the Zoroastrian massacres were not only at the hands of the invading Arabs, but happened through the centuries, like a relentless tide which crawls in slowly at first and then suddenly floods the shoreline. The religion of the rulers of multiple Muslim dynasties, starting from the Rashidun Caliphs (651 – 661 CE), through the centuries down to the Qajars (1785 – 1925 CE), overwhelmed the Zoroastrian religion and subjugated its people, whilst firmly establishing its own brand of Shia Islam. Each invasion brought about a new horror of destruction unseen until then. Barely two centuries into the second millennium, the most horrific series of massacres had reduced the population of Iran to levels so low, that it took another 800 years (mid-20th century) for Iran’s population to reach pre-Mongol invasion levels! This genocide of the Zoroastrians from the advent of Islam to the late 19th century, far worse than what the Jews have ever endured, is often absent from most world history books!

The Rashidun Caliphs (632 – 661 CE)

In the immediate years following the Arab invasion, some practices contrary to Islam were prohibited by the Caliphs. Initially, Zoroastrians were called “Dhimmi” (protected minority) and given the status of “People of the Book” by Caliph Umar (583 – 644 CE). When the city of Ctesiphon (in current day Iraq) fell in 637 CE, large scale arson was rampant. Palaces and their archives were burned. According to Al-Tabari, a prominent Persian scholar and historian who had memorized the Quran by age seven, when the Arab Commander Sa’ad ibn Abi Waqqas wrote to Caliph Umar asking what should be done with the books at Ctesiphon, Umar wrote back: “If the books contradict the Quran, they are blasphemous. On the other hand, if they are in agreement, they are not needed, as for us Quran is sufficient.” And so the huge library was destroyed and the books, collated by generations of Persian mathematicians and scholars were burnt or thrown into the Euphrates River. This was one of the first, of centuries of systematic annihilation of the Zoroastrian religious texts.

Nearly 40,000 captured Persian noblemen from Ctesiphon were taken as slaves and sold in Arabia. The Arabs called these Persians “Ajam”, meaning “mute”. When the people of the city of Estakhr, which was a religious center in the Fars region near current day Shiraz, put up a stiff resistance against the Arab invaders, 40,000 residents were slaughtered or hanged.

The Umayyad Caliphs (661 – 750 CE)

Within a hundred years after Yazdegird’s death, the Umayyad Caliphs had imposed the “Jiziya” (poll) tax upon the Zoroastrians. The official language of Iran was made Arabic instead of the local Persian. It was commanded that anyone found speaking Persian would be hanged by their tongue and have it pulled out. In 741 CE, the Umayyads officially decreed that non-Muslims should be excluded from governmental positions. Gradually the number of laws governing Zoroastrian behavior increased, resulting in restricting their ability to participate in society, and made life difficult for them in the hope that they would convert to Islam. As one of the Caliphs had remarked “milk the Persians and once their milk dries, suck their blood”!

Al-Biruni (973 – 1048 CE), a Persian scholar and scientist, in his book “Asar al Baghiyeh” has written about multiple gruesome incidents where so much Zoroastrian blood was shed as to run the water mills with it! An Arab general, Abdullah Ben Amir (622 – 678 CE), once ordered captives to be hanged on the two sides of the road for 24 miles (4 farsangs) upto Mazandaran, so that the victorious Arab army can pass through between them! The attack on Tabarestan (present-day Mazandaran) failed, but he managed to bring Gorgan under his control. He had vowed that he would kill as many Persians such that their blood mixed with water would enable the millstone to grind as much flour so as to produce one day’s meal for him. So many Zoroastrians were beheaded, that the watermills were run by people’s blood for three days and he fed his army with the bread made from that bloodied flour. But despite this, Tabarestan and areas near the Caspian Sea, such as Gillan and Dailaman remained unconquered until the majority of Zoroastrians converted to Islam gradually during the Safavid dynasty in the late 1500s or later migrated towards India.

The Abbasids (752 – 804 CE)

As the Abbasids came to power with the help of Iranian Muslims, the status of Zoroastrians was reduced from “Dhimmi” to “Kafir” (non-believers), as only Christians and Jews were considered to be the “People of the Book”. They were discriminated against and thought to be polluted. Fire-temples were destroyed and in its place mosques were set up. It was during this time of the Abbasid rule, that the Zoroastrians, though still large in number, were reduced to a minority for the first time in Iran. Those Zoroastrians who converted to Islam were called “Mawalis”, but they were also discriminated against by the Muslims. It was some of these converted people who then started taking advantage of the situation by siding with the rulers, while being vicious with their erstwhile brethren. It is from their conversion that you get the Parsi-Gujarati term “mawali”! If in a family one of the brothers became Muslim, the family property would automatically belong to that brother who had converted. To avoid such situations, other brothers would also outwardly convert, but the next generations would be born Muslims and the Zoroastrian faith would slowly disappear.

A Governor of Khorasan (the place from where the Parsis of India originate) banned publication in Persian and all the Zoroastrians were forced to bring their religious books to be thrown in the fire. It was a common practice to burn scholars in the same pyre where their books were burnt, or cut their fingers so that they could no longer write. Due to such acts, invaluable scriptures written in Pahlavi script were lost forever.

While Pahlavi books were being destroyed, Iranian scholars found a solution to save such books – they translated them into Arabic! One such rare book to survive was the “Khodai-namak” from the Sassanian era. It was translated into Arabic by Dadbeh “Ebn-e-Moghaffaa” under the title: “The Book of Kings”. Later, intellectuals like Dadbeh were burned alive by the Muslim clergy. Firdausi refreshed this book in Persian, expunged it of all Arabic words and called it the “Shahnameh”. Today UNESCO recognizes this as the masterpiece of epic poetry!

(Photo Source: wordsonimages)

There were Zoroastrian leaders like Babak-e-Khorramdin (795 / 798 – 838 CE) who fought for over 21 years. Babak had remarked: “Better to live for just a single day as a ruler than to live for forty years as an abject slave.” He was betrayed by an Iranian called Afshin and as a result Bakak was taken as a prisoner to Baghdad. As his limbs were cut off from his body, Babak is said to have drenched his face with his own bleeding arms so as to deprive the Arabs from seeing his face turn pale due to the loss of blood! He was then hung and sewn onto a cow’s skin with the horns as ear level so that his skull would be crushed as the cow skin dried out.

The Saffarids (861 – 1003 CE)

Under the rule of the Saffarids, the Zoroastrians lived under the leadership of their High Priest. The political center of the Sassanian Empire in Iraq suffered much destruction and confiscation of property. With lack of imperial patronage, the Zoroastrian clergy quickly declined after it was deprived of state support. The Zoroastrian nobility who voluntarily converted to Sunni Islam came to power. They were called the Samanids (819 – 999 CE). During their rule the fire temples were still found in almost all the provinces in Iran, including Baghdad. Historian Al-Masudi, a Baghdadi born Arab, records that the religion of Zarathushtra continued to exist in many parts of Iran as well as other regions including Sindh in the Indian subcontinent, which later came under Muslim rule.

It was during the reign of the Samanids that a group of Zoroastrians, in order to preserve their religious beliefs and customs, left the shores of Iran and made their way to India. They gave up all their worldly possessions for the survival of their faith. This group from Nishapur in the district of Khorasan and Sanjan (not to be confused with a similar sounding city of Zanjan in Iran) in the present day area of Turkmenistan, landed on the island of Diu off the coast of Gujarat in 936 CE. They stayed there for 20 years before they finally settled on mainland India and called the place they landed at, Sanjan, after the city of their ancestors.

The Sanjan Memorial in Gujarat

This first group of refugees was followed by a second one, and having procured their religious implements with them (the alat), consecrated an Atash Behram Fire (Fire of Victory) and called it the Iranshah – their King in exile! In addition to these Khorasanis or Kohistanis (mountain folk) as the two groups are said to have been initially called – at least one other group is believed to have come overland from Sari (in present-day Mazandaran, Iran). The establishment of another city in Gujarat “Navsari” i.e. ‘new Sari’ is a reflection of this Iranian city. After that, it is assumed, there were several smaller migrations from different parts of Iran into the same region of India. Later these refugees of the once mighty Achamenian, Parthian and Sassanian empires, came to be known as the Parsis of Western India.

As we shall see almost a millennium later, a member of this group of refugees played a pivotal role in the survival of those that were left behind in Iran, to face even more horrendous atrocities which were yet to rain down upon our Zoroastrian brethren, in the coming centuries.